The common file, as every workman knows, is an Implement, the flat or curved surfaces of which are notched or serrated in such a manner that, on being rubbed on the wood, ivory, metal, or other hard substance for which the tool is intended, a surface of more or less smoothness is obtained.

Files are made of bars of steel prepared in a peculiar manner, it being necessary that the file should be formed of the hardest possible metal, or else its working surface would be speedily worn away. The steel is therefore rendered harder than usual by means of a process known as double conversion, the metal thus prepared being said to be doubly converted.

Small files are generally made of cast-steel, which is for this purpose preferred to forged steel, on account of its fineness and quality. The larger kind of files are forged from bars of steel, which have been beaten into the requisite shape by means of the tilt-hammer. The largest kind of files, rather formidable looking tools, are forged from the bar steel, without the latter undergoing the preliminary process of tilt-hammering.

The files are then shaped—the square and flat ones by means of a common anvil and hammer; those of a circular, half-round, or triangular form by means of bosses or dies, made of the corresponding shapes, fitting into grooves made for them in the anvil.

The surface of the file thus prepared is perfectly smooth, but it has to undergo another process—that of softening—before it can be serrated or toothed. This softening, or “lightening,” as it is technically called, is effected by placing a number of blanks, as the uncut files are termed, in a large brick oven, made perfectly air-tight, to prevent the steel from becoming oxidized. The fire is made to play round the oven until the “blanks” are perfectly red-hot, when the heat is relaxed, and the oven gradually allowed to cool.

On the perfection of this process depends much of the value of the file, and the labor of the worker. If the metal be too soft, the indentations may be too heavy and irregular; if it be too hard, the workman will find much of his labor fruitlessly expended. After being softened, the “blanks” are carefully ground and smoothed down to the requisite shape, after which they are passed to-the file-cutters.

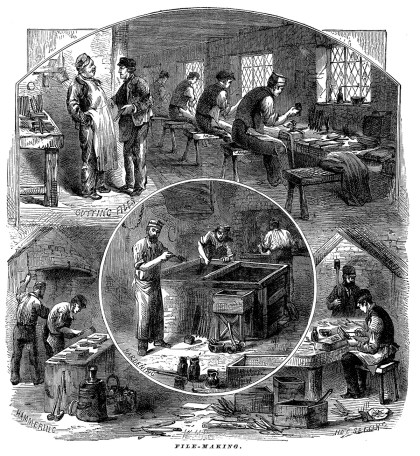

File-cutting is a curious and interesting process. The cutting-rooms are generally long, low apartments, with as many windows as possible, it being essential that the workman should have plenty of light, so as to immediately detect or prevent any flaw in the cutting. The work-benches are placed along the wall, just below the windows, each file-cutter sitting upon a stool, or astride a saddle-shaped seat, immediately in front of the bench.

Before each workman is a small anvil, fastened to the bench in such a way that it can be instantly removed if required. The cutter ties one of the blank files upon the anvil, securing it from slipping by means of a strap which passes over the ends of the file, and which is held tightly in its place by the weight of his foot. He then takes a peculiarly shaped hammer and a short chisel, rather broad in appearance, having a carefully ground edge, and formed of extremely hard steel.

If the file to be cut be a common flat one with broad indentations, the workman’s task is a comparatively light one; but if it be one of the finer kind, a wonderful degree of delicate accuracy is expected of him. If we take a common file, we shall find it covered cross-wise with a series of well-formed and strongly-defined indentations running parallel to each other. These are the result of the special training of the file-cutter. No unpracticed hand, even if assisted with every mechanical appliance, could compete with the productions of the regular workman, whose keen and experienced eye and steady hand are his sole guides in determining the relative distance of each groove or cut.

Indeed, according to a writer upon this subject, “so minute are these cuts in some kinds of files, that in one specimen about ten inches long, flat on one side and round on the other, there are more than twenty thousand cuts, each made with a separate blow of the hammer, the cutting-tool being shifted after each blow!” Such a file may be bought for a few dimes, the purchaser never dreaming of the vast amount of patient toil necessitated by its manufacture before it could enter the market.

The process of cutting varies somewhat with the shape of the file. If it be a flat one, the task of cutting is, as before stated, comparatively simple and easy. If it be a half-round one, the cutter still uses a straight-edged chisel; but has to make three or four cuts before a complete cross groove can be obtained. Chisels with semi-circular edges are used for cutting some varieties of round files; but even with these the straight-edged chisel is frequently used.

Various attempts have been made for the purpose of substituting mechanical labor for that of the artisan; and in America these efforts have proved in some instances successful. Still this is stoutly denied by some of the hand-cutters, who strenuously insist that file-cutting is a process which can not be properly performed by any kind of machinery, however ingenious or skillfully devised.

They state that machine-made files are, and always must be, inferior to hand-made files, and for the following reason: If one portion of the file be in any degree softer or harder than the other parts, the uniformity of groove, which constitutes the principal value of a good file, could not be maintained. The chisel would sink unequally into tho metal, and thus render the file worthless. It is only fair to add that the advocates of machine-cut files deny these allegations, and profess to have overcome the difficulties complained of.

After being cut, the files have to be restored to their original state of hardness. There are various ways of effecting this, each manufacturer having his own particular method. The process commonly adopted consists in covering the files with a kind of temporary varnish, or composition, to prevent oxidation and scalding of the steel when heated. The files are then heated uniformly throughout in a stove, from which, when they have reached the proper temperature, they are quickly withdrawn and suddenly plunged into a bath of cold water. The effect of this, properly performed, is to give them an extraordinary degree of hardness.

The concluding operations are very simple. The files are scoured for the purpose of removing the varnish, then carefully washed and dried, and finally tested; after which they are wrapped in stout brown paper, and passed into the warehouse, ready to be dispatched to any part of the habitable world.

The Manufacturer and Builder – January 1870

—Jeff Burks