The general demand for finely finished floors of hard or soft wood in modern residences has given rise to such a variety of tools and finishes designed for this special purpose that natural confusion arises as to the best tools, finishes or methods to employ in this highly important branch of the trade.

The growing demand for the conveniences of the city residence in the homes of the smaller towns and the rural districts often brings the carpenter and the painter up against this sort of work, demanding methods of treatment with which they are unfamiliar, and many a good job of floor has been spoiled or indifferently treated by otherwise good mechanics, simply because they lacked the knowledge or experience so essential to success.

It has been the fortune of the writer to have a somewhat extended experience in the better grades of modern floor finishing, and it is with the hope of affording some degree of general information to the craft that this discussion of the topic is undertaken. For convenience in treatment the subject will be considered with reference to the following elements:

1. The carpenter.

2. The tools required.

3. The laying of the floor.

4. Preparation of the surface.

5. The painter’s work.

6. Different varieties of finish.

7. Relative cost of floors and finishes.

8. Suggestions as to estimating.

Taking up the first phase of the subject, it may be stated that not every good carpenter can make a success of finishing floors; a peculiar degree of skill is required, of that sort which enables one to finish a surface as smooth and free from imperfections as fine furniture and to do this work under trying conditions and with sufficient rapidity to make it profitable. The hardest work about a building is to be found on a floor, and three days’ continuous labor of this sort will give lame back, sore knees and a wire edge temper to any but a saintly character.

This is no place for a man who is lazy or grouchy. For the average sized room give us two good natured, active mechanics who can keep tools sharp and hustle, and they will usually work to a better advantage than a greater number. The view Fig. 1 shows a team at work. If your carpenter cannot sharpen plane or scraper to a razor edge and cut a clean shaving every time the tool is put to the floor, better put him at another job. In addition to these qualifications it is highly important that the workman be endowed with grace sufficient to keep his temper when his freshly sharpened tools hit a grain of sand.

Floor finishing requires a good eye, a delicate touch and a sense of pride in perfect workmanship. Often a floor which appears perfect to the eye will be wavy, and have imperfections which show up badly through the finish which inevitably magnifies all imperfections. These imperfections can be detected often by lightly passing the finger tips over the surface and may be quickly scraped out as they are felt. “Feel your floor” as you work it; when eye and finger tips both approve you will usually have a good job.

There is a legal maxim which runs to the effect that “he who seeks equity must come with clean hands.” To this might be added the maxim that “he who seeks to do a good job of floor work must come with clean feet.” Many a beautiful piece of scraping has been ruined by unsightly scratches made by the shoes of thoughtless workmen, and very often the same workmen who are doing the work.

Soft slippers or stocking feet are preferable when getting the floor ready for the painter. If you think you must wear shoes be sure that they are scrupulously clean and that all nails in heels and soles are filed down smooth to the leather. Some may think this counsel superfluous: “Any good mechanic should know that much”; well, possibly, but they don’t all remember it out this way, and the hardest task we have is often to keep the floor clean for the painter after the carpenter is done.

Keep plenty of good, clean building paper handy, and use it liberally in covering the finished stretches of your floor; if likely to be walked over much put two or three thicknesses where the travel will be, and if the house be occupied let the boss carpenter be wise enough to “round up” the whole family and “shoe them” with a flat file until every nail is cleaned off which is likely to do damage.

If it is it new house put up the bars and keep all visitors and other workmen off the floors until the painter is through, else you are likely to have your labor doubled by the dirty feet of careless visitors. Above all, be sure that you charge enough for the job, for the more you charge the better the owner will appreciate the value of your work and the more care he will take to see that your floor is not abused.

Before leaving this portion of the topic let me refer in the most kindly spirit to another matter which is a legitimate subject for caution. A great many carpenters are unfortunately addicted to the tobacco chewing habit, and a goodly percentage of this number are careless about where they expectorate. It is very unpleasant for the owner of a building, and he usually makes it unpleasant for the contractor when his hot air registers are loaded up with tobacco quids and spittle left by the carpenter who finishes the floor. It is probable that few readers of Carpentry and Building would be guilty of such an indiscretion, but there are a lot of such fellows in Nebraska, and it is in the hope that this may meet their eye that this friendly word of caution is dropped.

There have been many tools devised for floor work, which are intended to reduce the labor to the minimum and make the job easy. I have never yet seen many of these which are successful. Of this sort are all long handled planes, sanders, &c., which are designed to be operated by the workman while in a standing position. Just as well understand, boys, that if you are to get a first-class job on that floor you must get right down next to it and put in the hard licks, relying on sharp tools and a willing disposition to get you out of it as speedily as possible. No intelligent mechanic would think of surfacing a casing or finishing a table top with a plane attached to a handle 4 feet long: no more can you finish a floor with any of these makeshifts. This brings us to a brief consideration of the tools required.

Jack and smooth planes are indispensable in finishing pine floors, though most well milled hard wood floors may be satisfactorily finished with the scraper if the stock has been well smoothed by the sander before leaving the mill. Most of the manufacturers of high grade flooring now give special attention to the surface finish of their product, and some of the material now on the market is a marvel of perfection in machine work. None is so perfect, however, as to dispense entirely with hand finishing, and nearly all lumber yard stock requires a lot of hard work to put it in condition.

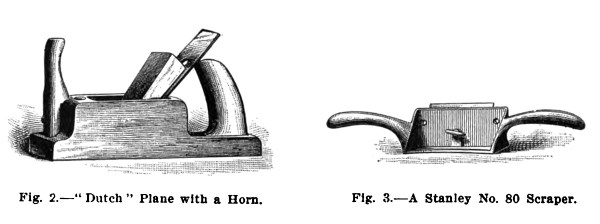

There may be cases in which the smooth plane and the sand paper will do the work, but plane marks will frequently show up on the surface, and it is safer to use the scraper freely. As to planes, every fellow has his favorite. Any plane is good that will do the work to the satisfaction of the user, but the writer confesses to a weakness for the old-fashioned Dutch plane with a “horn” on the front end. A home made tool of this kind, which is much more effective than handsome, is illustrated in Fig. 2.

This creation is the visible expression of a long felt desire for a plane that will “hug” the floor, run smooth, fit the hand and not “chatter” when a bit of hard grain is struck. In all these particulars it has proven a success. An ordinary 2-inch wooden jack plane was used to furnish the materials for it.

If partial to iron planes select one with a single cutter or a cutter without the ordinary cap which screws on to the bit. This precaution saves a deal of time in taking apart your plane for sharpening, and that’s an operation which will be frequently necessary. The Siegley plane is one of the best types of this tool and not expensive.

The scraper must always be the mainstay for floor finishing as well as all other fine wood work. This tool is of such great variety and form as to deserve more than a passing notice, ranging from the common cabinet scraper to more complicated tools of every description. One of the most common and universally used tools of this type is the scraper plane, in form resembling the smooth plane and having a scraper blade fixed in the stock in lieu of the ordinary plane bit. Another widely used tool is the “Stanley No. 80,” illustrated in Fig. 3 of the engravings.

Both the scraper plane and the “No. 80” are excellent tools in their place, but their place is not on the floor. Every carpenter knows that floor surfaces are more or less irregular and wavy and that while these irregularities are not so marked as to render it necessary to level the whole surface like a piece of plate glass, yet it is necessary to smooth up the joints and thoroughly clean the whole surface.

The peculiar character of the cutting edge of the scraper (which will be studied in detail later on) is such as to require constant change of angle and position in order to keep the tool cutting at its best without constant sharpening. The very strong “talking point” of the tools referred to—i.e., the plane surface next to the floor to serve as a guide to the tool and the rigid fastening of the scraper in the stock—are the two things which render these tools and all others of their class ineffective for floor work.

True that these tools are made susceptible of adjustment as to position of the cutter by shifting thumb screws, &c., but this takes too much time and experimenting before the proper position is secured to be of great value. That form of adjustment which is of most value will be one which can be made automatically by the hands while the tool is in use. Another defect of the tools under consideration is that they push instead of pull and cannot be worked up close to a corner or a baseboard.

I beg permission to say at this point that I have no interest in any tool manufacturing concern and no desire to give other than fair consideration to any and all tools offered to the trade for the purposes under consideration. The objections or criticisms which may appear in this article are frankly given as they have appeared to me or to workmen in my employ in practical use of the tools under consideration, all of which have had a fair and practical test in actual service.

Most veneer planes, &c., are excellent tools for their special uses in cleaning veneered doors, cabinet work and general bench work in the shop, but they have no business on a floor, and the mechanic who buys them for this purpose will waste his money and the time of his employer subsequently.

There is another class of scrapers equally good for floors or general wood work, which are equipped with a handle of convenient shape easily detachable from the scraper blade and adjustable to various angles as the case may require. These tools are generally designed to pull toward the operator and are so devised that both hands may find convenient hold of the tool.

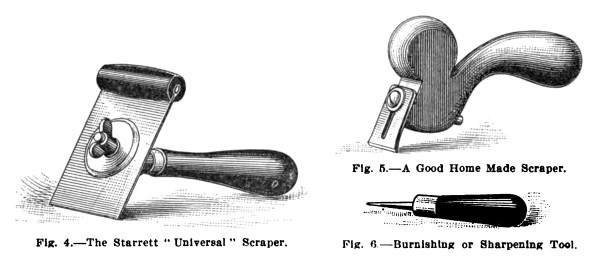

The chief criticism to be made on the various tools of this class now offered to the trade by tool manufacturers is that the scraper is generally made of too light gauge of steel and the handles bear every appearance of having been designed by some one who never pulled a scraper across a board. One of the best and neatest tools of this type is the “Starrett Universal,” shown in Fig. 4.

This tool is a marvel of cheapness when its quality is considered, and like all Starrett tools is so neat and convenient of adjustment that any mechanic should be glad to have one in his chest. The only criticisms I would offer against this tool are such as I frankly wrote the manufacturers some months since — viz.: that they strengthen the union of the wood handle with the ball and socket joint, provide a heavier blade, and substitute a ball fastening containing a nut for the thumb screw which secures the blade to the handle. I understand that the tool has been modified or improved along the line of the first two suggestions, but the thumb screw is still retained.

If the designer for the Starrett factory will spend thirty minutes on his knees in prayerful consideration of the needs of the craft and try for that length of time to use his “Universal Scraper” in actual work cleaning floors he will agree with me that the guard over the top, however useful as a protection for the hand, is utterly useless as a hand hold for the left hand, and he will lose no time in putting on the ball fastener where the left hand can get firm grip directly on the center line of draft.

This tool could be further improved for floor work if the manufacturers would furnish a special blade of heavy steel—say, about 2 inches wide and 3-32 thick, with a beveled cutting edge. Such a blade would cut faster and more evenly and not heat quickly.

The need of such a tool as this led the writer some five years ago to design and make for his own use a floor scraper illustrated some months ago in Carpentry and Building, which is here reproduced, Fig. 5, together with a convenient and easily made burnisher or sharpening tool. Fig. 6.

This tool is so obviously simple as to require little explanation or comment . It fits both hands, is easily adjustable to any position by a simple and automatic shifting of the position of the hand, will cut anywhere that any scraper will and some places that no other will, and can be easily and quickly made by any carpenter at a cost of but a few minutes labor. As shown it is equipped with 1¾ – inch blade as in actual use on a floor.

It will take any flooring that runs decently even, and in the hands of a man who is not afraid to work will clean and finish without the use of plane or other tool more square feet of floor than any tool that I have ever seen. While the blade is slotted so as to permit quick removal, not the least of the advantages of this tool is that it can be sharpened without removing the blade and the handle affords a convenient hold for the sharpening process. In actual use we rarely remove the blade from the handle unless to substitute another. The carpenter will find this tool convenient for cleaning plaster from the edges of jambs, for cleaning up quarter rounds and for a variety of uses.

That peculiar characteristic of the scraper “edge” which makes it necessary to frequently change the angle of cut in order to get the best service and avoid frequent sharpening is something which must be reckoned with in determining the good qualities of any tool of the scraper type. Always avoid a tool which demands some other tool to adjust it. As a general proposition the simpler the tool the better suited it will be for the purpose and a greater quantity of work will be the result.

(To be continued.)

Frank G. Odell.

Carpentry and Building – December, 1905

Bonus images:

Postcard showing flooring workers in France, turn of the 20th century.

French medical photos of the bodily deformations suffered by floor finishers.

—Jeff Burks