Working with wood has always seemed like it’s something more than just refashioning dead vegetable matter into useful items.

Unlike metal, wood has a way of reminding us of the time it took for every stick to grow. Pick up a door stile and look at the end grain. Count the annular rings and you know it took 40 years to make that part for a cabinet door. A door panel might take 100 years to grow. I have a piece of slow-growth huon pine in my shop that is about 4” wide and took more than 300 years to grow.

If you respect your elders, we all need to tip our hats to the scrap bin every day.

But I don’t think of time and lumber as mere linear things. Perhaps it’s my affinity for Buddhism, but I have always suspected there is a circle behind the work I do. But that the circle is so big that I am like a gnat walking along the rim of a dog bowl and unable to see that my path curves upon itself.

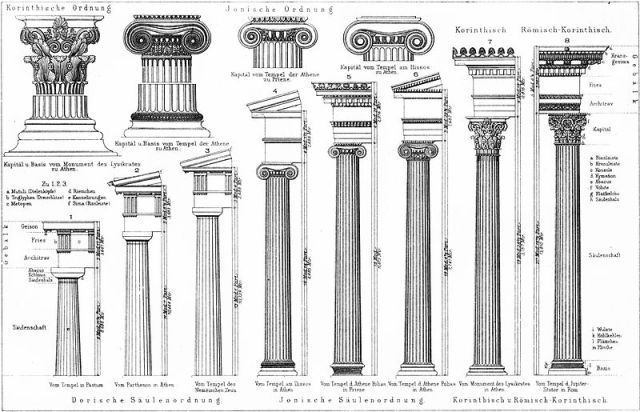

This week I’m reading a fun little book that has been fertilizing my circular logic. “The Lost Meaning of Classical Architecture” by George Hersey (The MIT Press) seeks to unpack historical architectural terms – torus, dentils, triglyphs and echinus, for example – and explain their connections to early Greek and Roman culture.

While Hersey explores a lot of fascinating ideas, the ones that stuck in my mind relate to Greek ritual sacrifice. Temples are in many ways a man-made grove of sacred trees, according to Hersey. Temple columns represent many things, including both a sacred tree and the human body.

In a ritual sacrifice, the animal victim is taken apart. Certain parts, such as the head, thighs, feet and horns are given special treatment. Some parts are eaten. Then the victim is reassembled on the altar. The head might be hung on a stick and draped with the skin. The bones might be arranged as they were when the animal was alive.

Without getting too deep into the religious aspect of it, the animal was the vessel of god during the sacrifice. And reconstructing it could represent that it has been reborn, or is immortal or wasn’t killed in the first place.

Whew. Should I insert a fart joke here?

When I make a piece of furniture, I am struck by weird and uneven aspects of the process. We take this massive entity – a living thing that took hundreds of years to grow, and we quickly girdle it and end its life so fast that it can take a week for the leaves to get the message that they’re dead.

We work these bits into ever-smaller chunks, getting down to the parts that are the strongest or most beautiful.

Then we rebuild these small bits into ever-bigger and more massive assemblies. We join them so they are as strong as when they held the forest canopy aloft.

And if we are successful, our work might last as long as the tree itself lived. It feels a lot like the description of Greek ritual sacrifice in Hersey’s book.

The implications of this view of the craft are personally staggering. Are we priests of a pagan religion? Are we recreating trees to give them immortality? To prove we never killed them?

Or is it as simple as when you spend hours at a bench every day sawing and planing a material for 20-plus years, that you get a little funny.

— Christopher Schwarz