Every boy ought to know how to drive a nail and saw a board. Somewhere in connection with every well-ordered home there should be a workshop of some sort. An article could easily be written treating exclusively on the advantages accruing from even a slight dexterity in the use of a few tools, and it could easily be shown that these advantages are by no means confined to artisans, but that professional men and men of affairs find healthful exercise, pleasant diversion, and mental discipline “over the bench.”

But omitting all that, we start now with the postulate that a boy ought to have a workshop, and the only question for present consideration is how it ought to be fitted up. As the chief purpose of the boy’s workshop is rather to give the boy plenty of congenial work than for the sake of the work the boy will do, the more of the work of fitting up the shop that is left to the boy the better. We put four “works” in that sentence, and we are glad of it. Happiness depends almost wholly on occupation. Professor Albert Hopkins once gave as his idea of happiness, “right activity.”

If a boy is going to make a collection of postage-stamps, and you want to spoil all his true pleasure, give him a patent album, a set of the catalogues of all the dealers in the world, a thousand dollars to spend, and a clerk to write his letters and classify and paste in his stamps.

If you want to spoil a boy’s interest in trouting, buy him a thirty-dollar rod, a dozen well-stocked flybooks, and send him off on an expensive journey. The fellow who gets the most fun out of fishing is the one who gets up in the morning before the sun, digs a cinnamon-box full of worms behind the barn, cuts a little pole from that clump of delicate birches on the hillside, and tramps off mile after mile along a jolly New England brook, using his pocket for a cracker-basket, and stringing his trout on a willow stick.

This has to do with the question of fitting up a boy’s workshop. If you want to fix the boy so he will never do any work, put him in a fine room and have a carpenter make for him an elaborate bench; give him a complete “kit” of tools, and let the carpenter make all the cases and devices necessary to keep them in.

The trouble with this method is that it takes all the personality and all individual interest out of the work before he is ready to begin. Of course it saves you the trouble of lending yourself to your boy, and it is for you the easiest way, perhaps, to get the matter off your hands; but it is like a uniform use of checks for Christmas presents.

The first requisite is a good room, well lighted, not too much exposed to heat in summer, and, if possible, capable of safe warming in winter. Next, we must have a few tools;— and let them be of the best. They may be bought as a set in a chest; but it is much better to select them one by one with the friendly advice of some good workman. They may be thus selected and stowed in a chest specially made for them, and then presented to the boy who is to use them; but a much better way is to get the boy interested in their selection, and let him accompany you and the workman and assist in their purchase.

No father is so wealthy, so famous, or so busy that he can afford to delegate to any one else the larger share in the interests of his son. Affection is largely dependent on the sharing of common interests; and since the child is not able to understand his father’s business, it becomes necessary for the father to keep himself always personally interested in the pleasures and small businesses of his child.

We must have a hammer. This tool needs careful selection, as do the more expensive cutting tools. Its weight must be adapted to the strength of the workman; it must be a well-shaped, straight-grained handle, firmly fastened to the head, which should be of good steel. I mention this as many have an idea that anything will do to pound with. For a combination pounder and cutter we shall need, of course, a hatchet.

Three saws will do to begin with. A cross-cut saw, which is one of the most important tools in the shop, and which requires much care in its selection and more in its use; a “rip” saw, used in sawing boards lengthwise, and a mitre saw, for making clean, narrow cuts. It may be well to add a fret-saw.

A brace and its accompanying bits will follow. Probably none larger than an inch will be needed; but it is good economy to have all the smaller sizes. Among the pet tools of the carpenter must be reckoned the chisel. There should be at least three of them having widths of an inch, half-inch and quarter-inch. A set of curved chisels or “gouges” should accompany them and, of course, a strong mallet. Both chisels and gouges should have handles fitting into sockets in the shafts of the cutting parts. For measuring and testing our work we will procure a two-foot rule, a square, try-square, gauge and a pair of dividers.

Three planes will answer the needs of our young workman. These are a “jack-plane,” for the rougher work of rapidly reducing the surface of the wood; a smoothing plane, for finishing the work and for planing the ends of boards across the grain; and the “jointer,” which is a long plane used for rendering the edges of the wood true, so that nice joints can be made. Add to these tools a good supply of brad-awls, a scratch-awl, a screwdriver, lead-pencil, and above all, a good knife, and we have enough to set up with.

As everything depends upon the care which the tools receive, and as the construction of a good box is not within the power of a tyro, it is well to procure a strong chest fitted with a few compartments to hold the outfit. The chest should be twice as large as seems at present necessary, that it may hold the new tools that will gradually be added.

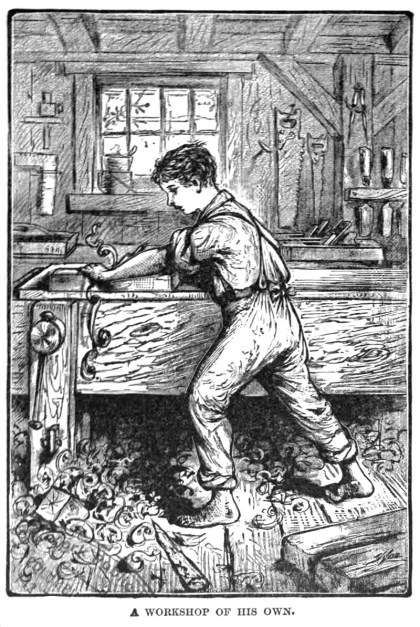

The next thing in order is the bench. This the boy should be encouraged and assisted to construct for himself. We advise him to take much pains with it. His future comfort depends largely upon it.

Visit the shop of the best carpenter in your town and study the bench he has made for himself. Notice how he has selected well-seasoned stuff, “clear,” straight-grained and well-dressed. Observe how firmly it is put together and braced, that it may stand all kinds of strains without becoming shaky. Be sure to make it of a height suited to your stature, a trifle too high for you if anything, as you are growing rapidly.

Give particular attention to the devices, at the left-hand end as you face it, for holding the end of a board to be planed; and also study carefully the attachment of the wooden vise or “bench-screw.” The first test of your ingenuity will be found in the way this bench-screw operates after you get it attached to your new bench. If it opens, in response to the revolving handle with a smooth, steady motion, and then at your pleasure closes upon your board with a calm but unrelenting grip, you may toss up your cap and cry “Victory!”

The first one I set up didn’t work that way, but opened in an uncertain, haggling manner, like an obdurate bureau-drawer, and when it was screwed up as tight as possible had a way of suddenly relaxing its hold and letting the board down at the most inconvenient moment. This screw I did not include in the list of tools proper, but it is almost as necessary as any of them, as also are a grindstone and an oilstone for sharpening your steel, and a large tough block on which to rest whatever you wish to dress with the hatchet.

I have intentionally omitted the turning-lathe and the foot-power scroll-saw, believing they belong, if anywhere, to a later stage in the young workman’s career. Space is lacking at this time to give detailed directions for making such simple articles as are suited to a beginner’s capacity, but, as a rule, it is better to begin by repairing broken articles than by attempting to make new ones; and after a little insight into methods of construction has thus been acquired, it is best to make articles of use about the house, rather than the merely ornamental knick-knackery.

The American Thresherman – December, 1907

—Jeff Burks